Astronomers have discovered a puzzling planetary system that doesn't fit theoretical models

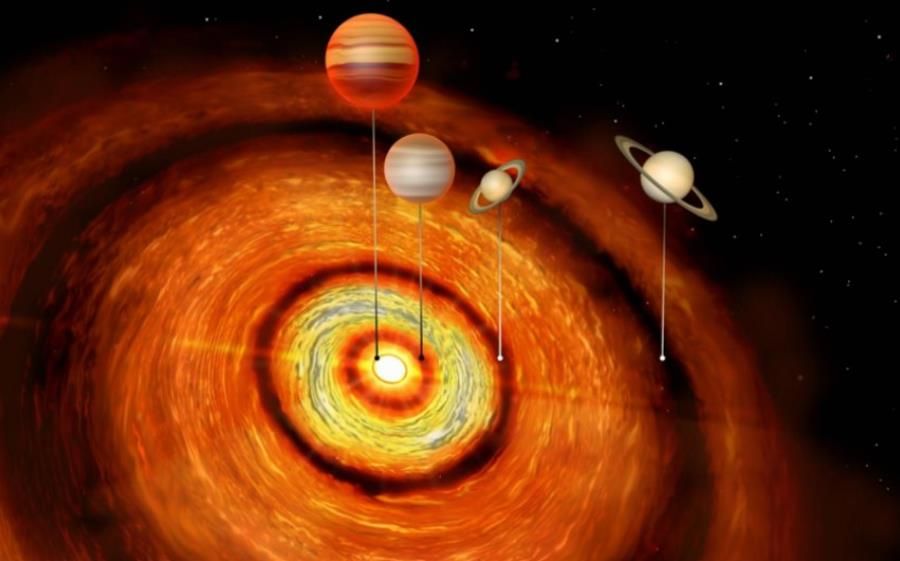

In the orbit of a young star, scientists have discovered four planets the size of Jupiter and Saturn. This is the first time so many massive planets have been observed in such a young planetary system. This system also has a record range of orbits – the outer planet orbits more than a thousand times farther from its star than the one closest to it. The observations raise questions about how such a system could have formed?

The star in question is relatively young, only two million years old. You could say that in astronomical terms it is „bean”. It is surrounded by a protoplanetary disk of dust and ice – a place where How planets, moons, asteroids and other astronomical objects form in planetary systems.

This star had already been recognized as unique when the so-called "protoplanet" was located in its orbit. of a hot Jupiter. No such objects have been observed before in the orbits of such young stars. Hot Jupiters are a class of extrasolar planets, gas giant which The exoplanets' orbits are very close to their parent star, often much closer than Mercury's orbit in the Solar System.

Hot Jupiters are among the first to be spotted by astronomers in exoplanets. Because of their size and a short orbital period, planets in this class are much easier to spot when transiting against their parent star. But their existence has long puzzled astronomer in, as they are believed to be too close to their stars to have formed in that particular location.

Using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) observatory, the team The scientists at the University of Cambridge found a sibling of this young hot Jupiter. During the observations, the researchers noticed three distinct gaps in the protoplanetary disk, which re pointing to three more gas giants orbiting around young star. The results of the observations are presented in „The Astrophysical Journal Letters”.

The young star, CI Tau, is located about 500 light-years from us in a highly productive region of the galaxy known as the "Tau Galaxy". stellar nursery. Its four planets have extreme different orbits. The closest is within orbital distance of Mercury in our Solar System. However, the farthest planet orbits at a distance more than three times that of our Neptune. The two outer planets have the mass of Saturn, while the other two in inner orbits have masses of about 1 and 10 Jupiter masses, respectively.

Observations raise many questions for astronomers. Scientists estimate that about 1 percent of. all stars have hot Jupiters, but most of the known planets in this class are much older than CI Tau.

– It is currently impossible to say whether the extreme planetary architecture seen in CI Tau is common in systems hosting hot Jupiters, because the way The way these sister planets were detected, i.e., by their influence on the protoplanetary disk, would not work in older systems in which two outer planets had hich no longer have such a disk – Professor Cathie Clarke from the Cambridge Institute of Astronomy said.

It is not r It is also clear whether planets have played a role in driving the innermost planet to its ultra-tight orbit and whether this is a mechanism that ry leads to the formation of planets of this type. Another mystery is how in the og that the two outer planets have formed.

– These planets do not fit into theoretical models of planet formation, because these models focus on types of planets that have already been observed. Saturn-mass planets should have formed first, forming a rocky core and surrounding it with a layer of gas . However, these processes should be very slow and at great distances from the star – Clarke explained.

Astronomers will now study this puzzling planetary system in r The observations have been taken in different radiation bands to give us more clues e have been studying the properties of the protoplanetary disk and the planets in it.

Source background: University of Cambridge, photo. Amanda Smith, Institute of Astronomy, University of Cambridge